Does Everyone Have a Specific Calling?

Part 4 in a series on vocation

Last time I suggested there is a clear answer to the question, “Do all have a vocation?” If we take the Bible seriously, then each of us has at least two — the human calling to rule in cooperation with God and the Christian calling to restored life with God through Christ.

Those are general vocations, though, applying to all alike. Do we also each have a more specific call tailored to us as individuals? In an article on calling in Relevant, Karen Yates notes that this assumption is common in evangelical circles. She describes leading a study with a group of women during which the study author asks, “What has God uniquely called you to do? Are you fulfilling God’s calling on your life?”

Has God in fact uniquely called each of us to a particular task?

Three Modes of Response

Before trying to answer that question, it would be helpful to consider the mechanics, so to speak, of calling more closely.

Conceptually, there are three distinct ways God can relate to us and to which we can be responsive. First, God can command, and we can obey, or not. Second, God can invite, and we can take him up on the invitation or decline to do so. Finally, God can set us within a certain context to which we then respond.

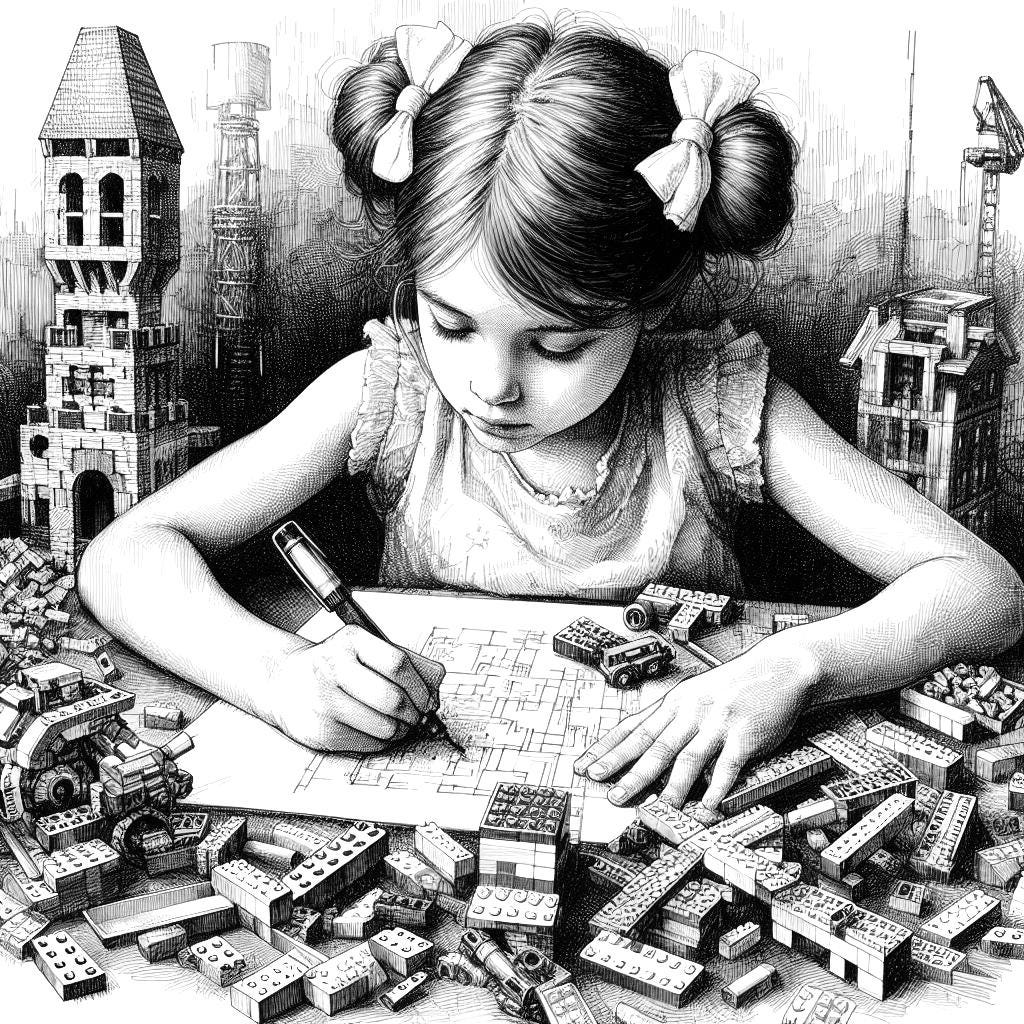

An analogy might help. When my kids were younger, I related to them in each of these three ways. Sometimes I would command: “Kids, get dressed. We’re going to the Johnsons’ for dinner.” Often, I would invite: “I’m walking over to the park. Would you like to come?” And more often still, I would furnish a context: “Look - I bought you a new Lego set!” In this last case, I wasn’t telling them to do anything or even inviting them to something specific. Rather, I was creating a setting, giving them resources for creativity and exploration, and leaving it entirely to them what they would do with them.

God interacts with us in these same ways. Consider some examples from scripture. The initial creation mandate is in the form of a command. God doesn’t say, “Hey, would you guys like to be fruitful and rule this planet?” He commands humans to do so.

There are also invitations. Jesus says, “Come to me, all you who are weary and burdened, and I will give you rest.” (Matthew 11:28)

There is creating a context. In placing us in a position of stewardship over the earth and giving us a particular nature and a specific physical constitution, he does not tell us how to order things. Rather, he puts an incredible abundance into our hands, like the world’s most extensive Lego set, to see what we’ll make of it.

We are liable to speak of all three of these modes in terms of vocation (or calling). When Paul on the road to Damascus experiences a dramatic intervention of God and subsequently a specific commission, we recognize this as a calling. Paul himself certainly spoke of it in this way. (See 1 Corinthians 1:1, for example.)

Then there are invitations that those who experience them will tend to describe as vocations. Consider what happened to Hannah Hurnard, author of the classic Hind’s Feet in High Places. One afternoon, she was walking in a remote place in Ireland when she experienced something that would change the course of her life:

“Up there on Ireland’s Eye, I had no special subject in mind, and began to read just where the Bible opened, which happened to be the ninth chapter of Daniel. As I slowly read through this wonderful prayer, pondering on it verse by verse, an unexpected and startling thing happened. A thought came into my mind, as though naturally following the train of previous thoughts, but with a clarity and significance which seemed a personal challenge.

‘Hannah, would you be willing to identify yourself with the Jewish people in the same way, if I asked you to?’

I found my thoughts answering him in great distress. ‘But, Lord, I’m sorry to say I don’t like the Jews a bit. They ar the last people in the world I feel interested in trying to help. How could I be of any use as a missionary to the Jews if I don’t like them?”

‘If you will yield to me wholly and agree to go, I will make you able to love them and identify yourself with them. It all depends upon your will.’

I scrambled to my feet and knelt down on the rock which had become an altar, for this was a definite offering of myself, an act of deep worship and glad surrender. It concluded a conversation and sealed my readiness to obey. I knelt then on the rocks and said, ‘Here I am, Lord. I will go as a missionary to thy people Israel.”

Finally, we can feel drawn to respond to our context in a particular way and describe this as a calling, too. Note that “our context” includes not just the world around us, but also the particulars of our selves and experiences. Many write about discovering a sense of vocation through attempting to forge a congruence between who they are and their role in the world.

Parker Palmer, whom I quoted last time, has this sort of thing in mind when he writes, “Our highest calling is to grow into our own authentic selfhood, whether or not it conforms to some image of what others think we ought to be. In doing so, we find not only the joy that every human being seeks but also our path of authentic service in the world.”

Even thoroughly secular people often recognize and embrace this way of thinking about vocation. Novelist George Orwell, for instance, in describing why he became an author, writes,

“From a very early age, perhaps the age of five or six, I knew that when I grew up I should be a writer. Between the ages of about seventeen and twenty-four I tried to abandon this idea, but I did so with the consciousness that I was outraging my true nature and that sooner or later I should have to settle down and write books.”

The basic formula is this. There is a way I am made and some task in the world that fits it. Again, in the language of Frederick Buechner, “Vocation is the place where our deep gladness meets the world's deep need.” This kind of congruence connects deeply with us on an emotional level, it is natural to find ourselves saying things like, “This is what I was made to do,” or “This is what I must do.”

With these three modes in mind, let’s return to the question with which we began — Do all have a specific calling?

The answer will depend on which of these three we are thinking of. Surely the first type of vocation, the command, is rare. We read of many such cases in scripture, but we are reading about them because they are unusual. There are not many Noahs, Davids, and Pauls. Outside of scripture, there have been many individuals in the history of the Church who have also encountered God’s call as a clear command, but, again, it is a relatively small number. These are the people whose biographies we read because they have unusual lives.

The second type of vocation, the invitation, is more common. How common? I can’t answer this with any precision. I do know, however, that I have known many people who claim to have experienced something like this and I have experienced it myself.

The third type of vocation is potentially universal. Each of us is placed in a context. If we accept the sovereignty of God, we believe that our constitution and the circumstances of our lives are ordained by him. As David puts it in Psalm 139, “You created my inmost being…All the days ordained for me were written in your book before one of them came to be.”

Thus, in a very real sense, whatever we do in life is responsive to the context in which God has placed us. It is open to anyone to discern what sort of response to the context in which he finds himself is most appropriate and most accords with his sense of self. If it is right to talk about discerning fit as discovering one’s vocation, this is a type of vocation available to all.1

Notice, however, that the third type of vocation is specific in one sense — it is my identification of a way of life that is congruent with how I am made and the context I encounter; However, it is not specific in another: there may be many ways I could respond that would be equally congruent. In this respect, type three is quite different than types one and two.

Some Implications

So does everyone have a specific vocation? If we mean type one, it seems not; If we mean type two, also probably not (but maybe); if we mean type three, probably yes. Beyond answering this question, however, the distinction between these three types has implications for two related matters: How we should discern God’s call and how we should respond to it.

Discernment is the process of figuring out what my vocation is. This is an area where many people feel a lot of stress, searching for a clarity that feels elusive. Karen Yates describes the pattern this way:

“We have an expectation that our calling is discoverable. It’s the gold nugget buried within the river bank. Search for it, be patient, don’t give up, we’ll find it (or stumble upon it) one day, eventually, and our lives will never be the same.

We wait around for the phone to ring. Literally, to “feel called.” Or bump into it at random—the clouds align and a cross shines on the pavement before us—like the four-leaf clover underfoot, we sift, searching for that one thing we are “meant to do” that nobody else can make happen (unless, of course, God equips or enables or chooses someone else for the job).

For some of us, no matter how long we wait or how hard we search, the elusive “calling” doesn’t come. We look upon people living out their calling with envy—what’s wrong with us that we don’t know what we’re supposed to do with our lives? Why does He have something unique for them, but not unique for me?”

Notice the assumption: there is a singular thing God wants us to do, and this thing is our vocation. This assumption is appropriate if we’re talking about type one. But the examples we have of that kind of calling are ones where God’s commissioning is pretty clear. What we certainly don’t see is individuals taking the initiative to engage in a process of discernment to figure out what their calling is. David didn’t journal or take a spiritual gifts inventory before concluding maybe he was called to be Israel’s king. Moses was simply minding his own business when God broke into his life and sent him on mission.

On the other end of the spectrum, the initiative in discernment with type three vocation seems to lie much more with the individual. Here there is a natural place for questions like What am I passionate about? and What are my skills?, which are irrelevant when it comes to type one.2

This matters practically since we are bound to experience a good deal of frustration if we are expecting and trying to discern a type one calling when God is not calling us in that way. The process of discernment differs depending upon the type of call. As we noted above, there is not one unique thing we will discover if we are talking about type three vocation. Rather, it is a matter of discerning ways of being in the world that are more or less fitting given who we are and the context we face.

The response called for also differs. For type one, it is a matter of obedience. Refusing the call is rebellion, as in Jonah’s story. For type two, we may decline the invitation in question and are not disobedient if we do so (though we might be missing out on something very good).

With the third type of vocation, discerning a fitting response to the context in which I am placed is a matter of stewardship. Am I using the opportunities given to me well? (See the parable of the talents in Matthew 25.) This is obviously a complex matter, however. Again, it is worth emphasizing that it is unlikely there will be one uniquely best way to respond well to my context.

The framework sketched here might be liberating or disappointing.

It is liberating for those who, as Yates describes, are laboring under the frustrating burden of finding their one, unique calling from God so they can ensure they are fulfilling it and not wasting their lives. For such a person, the message here is this: You may not have a type one or two calling. If you do, God will surely make it clear. In the meantime, you are free to creatively (and courageously) respond to your context, and there is no single right way to do so.

It is potentially disappointing for those who long to be a Moses, David, or Paul, dramatically called out by God and sent on a mission. Our current cultural context that raises us on the mythology that each of us can be anything we want doesn’t help. As Yates writes,

“We have an expectation that our calling will be profound. We want to become instant successes, start a business, invent something unique, write a book that impacts thousands, raise the next Margaret Thatcher, write music that reaches the Billboard Top 100, become the next Rick Warren, or make movies that matter. We’re a culture consumed with numerical impact, with skyrocketing ROI, awards and the recognition of man, so when our “calling” is to be in the shadows, it’s a tough pill to swallow.”

But it’s a good pill to swallow. We’re not here to be much and to be big, but to be faithful in our responsiveness to God. I think Yates’ perspective, with which I’ll close, is helpful here:

“I think about some of the people new to our church, who are breaking through strongholds, walking in recovery and making tiny strides toward a better life. Most of them are living in the now, in the everyday questions: Will I have enough money at the end of the month? Will I stay clean? Will I get to see my child one day? They take each day one step at a time, one step closer toward their best selves, the people God wants them to be.

This is how I’ve started looking at calling.

It takes an extraordinary amount of discipline and maturity to live in today, walking step by step, doing whatever I’m supposed to do today. It takes discipline to say “I don’t know.” It takes faith to trust in one-day-at-a-time. It requires me to lay down my desperate, freakish desire for control and trust He is at work.

He knows the reason I was made. If I walk in step with Him every day, I will walk into the reason. Maybe I’m here for something big and meaningful, or maybe I’m supposed to pick up rocks so the tractors don’t break.”

This is part three in a series on vocation. In case you’re picking up the thread in the middle, here are the previous posts:

Is it right? Or should, perhaps, the word “vocation” be reserved for types one and two — or even just for type one? That’s an interesting question, but I won’t attempt to settle the matter here. I do think it is useful, however, to bear in mind which kind of vocation we’re talking about in a particular case.

Moses wasn’t thrilled about the task assigned to him and was conscious of the fact that he lacked the requisite skills. Those things are beside the point when God commands one to go.

Great article John! Living in the shadows and doing the mundane is especially hard in today's world. It does take a lot of discipline. We have all the distractions of being able to see what else is out there and other's successes, then start to question ourselves, "Am I doing the right thing?"

This is an incredibly helpful framework. Thank you, John.